Agile methods for software development are widely used in the IT industry and are in many cases accepted as the "de facto" standard for effective product development. However employing Agile in an organisation is not clear cut. Many organisations are sold Agile methods as the answer to all their problems only to find that after a good deal of investment, in both time and money, the advantages that they were promised are not being realised. So why isn't working?

The truth is that Agile is not a solution in itself, in fact Agile is a set of principles (

http://agilemanifesto.org/principles.html) which can be applied to facilitate a very effective way of working. In some cases focus is placed so heavily on using what is considered Agile methods, that we forget what we are actually trying to achieve. This is where we have to remind ourselves that our aim is actually to deliver a product to our customer on time, on budget and at the right quality.

Changing the processes in an organisation is not easy regardless of which methods you intend to implement, and we can be sure that the hardest things to change are not the processes but people. The capability and motivation of the people in the organisation are central to success.

So how Agile do you have to be before you can call your organisation Agile?

Waterfall and Agile

Often there is a lot written about Waterfall versus Agile methods of development, however this may not be a very good comparison. The original "pure" waterfall model (Winston W Royce 1970) may be considered a static model with a "plan everything up front" method. However since the late 90s the use of iterative and incrementive models have been widespread with each iteration resembling a mini-waterfall. Even Agile still adheres to the good engineering practice of Specification, Design, Implementation and Test in a sequential order.

The real difference with Agile is that it includes aspects of the "project/product management" domain while traditional models are more focused on the technical development process and consider the "project/product management" as a separate domain.

It is also worth considering that there is no "one size fits all" for software development. Each product and organisation has its own characteristics, capabilities and constraints. In many cases a hybrid approach may be required with an organic growth towards Agile. Performing a "big bang" change to an organisation can be costly when migrating to any new process.

Know your Business Model

When migrating to an Agile model it is very important to consider the type of business model for the product or the organisation. This has a big impact on how the Agile process will be implemented. Failure to consider the business model can result in the Agile process simply not working or a long journey of trial and error to make processes fit.

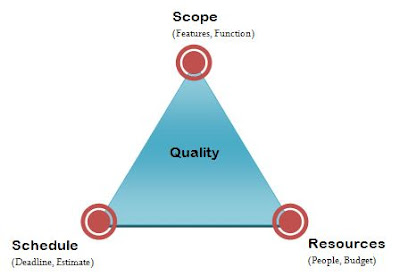

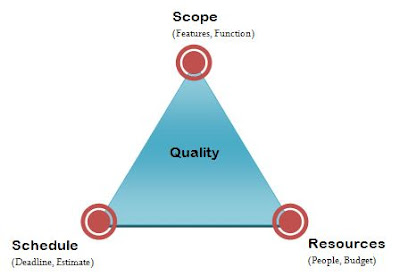

We can consider the Iron Triangle (Dr. Martin Barnes) which shows the constraints of Scope, Schedule and Resources in project management. This shows that a change in one of the constraints has an effect on the other two. So for example, a reduction in Scope may result in a shorter deadline, or an increase in resources any allow for more features . But why is this important for Agile?

If we are running a business model which allows us a lot of freedom with Scope we can run a "line based" approach. This runs rather like a production line where we have a schedule determined by sprints and scope for delivery is negotiable. The host organisation has to have a good degree of influence over these constraints. Releases of the product are frequent and contain features which can fit into the defined budget and schedule. This allows us to quickly react to change since we can determine scope at the beginning of each sprint. This is a model which suits organisations providing products to a general audience where the product is purchased perhaps on licence or subscription. The decision regarding scope lies solely within the organisation.

On the other hand if we have a business model where the scope and deadline is often fixed we would probably want to run a "project based" approach. We can still use many of the Agile principles and tools but we are required to perform more planning up front. Deliveries from sprints may be more internal in nature rather than production quality since the final production delivery is dictated by the deadline. There is a reduced ability to embrace change since the constraints are not as flexible. This is a model which appears in organisations which often work to a contract. These constraints are given in a contract between two parties and must be adhered to legally.

If we are running a business model which allows us a lot of freedom with Scope we can run a "line based" approach. This runs rather like a production line where we have a schedule determined by sprints and the scope is negotiable. Such a host organisation has to have a good degree of influence over these constraints. Releases of the product are frequent and contain features which can fit into the defined budget and schedule. This allows us to quickly react to change since we can determine scope at the beginning of each sprint. This is a model which suits organisations providing products to a general audience where the product is purchased perhaps on licence or subscription. The decision regarding scope lies solely within the organisation.On the other hand if we have a business model where the scope and deadline is often fixed we would probably want to run a "project based" approach. We can still use many of the Agile principles and tools but we are required to perform more planning up front. Deliveries from sprints may be more internal in nature rather than production quality since the final production delivery is dictated by the project deadline. We may expect stabilising sprints during the development. There is a reduced ability to embrace change since the scope may not be flexible. This is a model which appears in organisations which often work contract based, where the constraints are given in a contract between two parties and must be adhered to legally.

Good Engineering Practice still applies

One of the principles mentioned in the Agile manifesto that is often misinterpreted is "Working software over comprehensive documentation". In some cases this can often be wrongly interpreted as "no documentation required as long as the system works". Documentation is an essential part of ensuring that a system can be maintained effectively. Without documentation we create a situation where we are dependent on "people with key knowledge" to maintain the product. This represents a serious risk for product maintenance whether we run Agile or not.

Concrete Principles which help Agility

Regardless of whether you are running "line based" or "project based" approaches there are a number of concrete principles which can help our organisation become more Agile. Below are some principles which can help agility.

"encourage transparency"

With an open and transparent culture, risks and opportunities are quickly identified which also means that they can be quickly addressed. Removal of a "blame" culture will help teams to be self organised since individuals will be more likely to take on responsibilities. Tools such as Burndown charts are easy to understand and clearly communicate the status of development to all stakeholders.

"deliver frequently"

The use of sprints and frequent deliveries ensure that the team is constantly working towards a short term goal and this gives focus. This allows us to regularly monitor both quality and delivery precision. If we start missing our deliveries or the quality of the deliveries are not up to standard this becomes apparent very quickly. We can then make adjustments and monitor the effect in the next sprints.

"commitment to deliver"

In order to successfully make frequent deliveries the there has to be a commitment to deliver from everyone involved. To gain this commitment everyone has to be involved in the planning process. If the whole team are involved in defining the scope and time estimates, there will be more commitment to deliver. Even at company leading levels there have to be clear overall goals and realistic plans. If the requirement on the team is unrealistic the team will lose their commitment since they feel there is no realistic chance of success.

"do only a few tasks at one time"

Getting a working release (internal or production quality) completed is very important. It is at this point we can really test and evaluate the progress of development. In order to get working releases we need to make sure we complete the tasks we are working on and this is why it is much more advantageous to have a few tasks fully completed rather than a large amount of tasks only half completed. A half completed task adds no value and hinders the delivery of a release.

"cut waste, continually improve"

In order to be Agile we have to continually ask ourselves what is adding value to our product and how we can improve. This is a continual process of fine tuning and keeps the development process aligned with the business. A good way to consider this is to think about which tasks add value to the product and which tasks do not add value to the product. Then consider if we can reduce the amount of time we spend on the "non-value added" tasks.

Practical implementation of an Agile Process

Agile can sound very easy to implement until you start to apply it to the organisation. Like any change in process there are likely to be problems and challenges since no single product or organisation is exactly the same. Each organisation has its own set of capabilities and legacy processes. The degree of change to be made has to be balanced with the required investment and long term gains.

It is important to give the change in process time to settle but at the same time if something is clearly not working take action. How well the Agile process fits is often related to the type of business model the organisation has. Below are some issues an organisation may face in a migration to Agile.

"owning the product"

The Product Owner is a key role in Agile and controls the starting point of the process. It is very important to ensure that product ownership works well. The Product Owner specifies the requirements and maintains the backlog. In order to gain a long term view of investment it is also wise to ensure that the Product Owner is responsible for maintaining "wide estimates" on the backlog. Just like any other development process if we get the requirements wrong we will be looking at expensive changes.

"up front planning"

The amount of planning we need to perform up front is related to the flexibility of our project constraints. The tighter the constraints the more planning will be required. Even where we are running a "project based" model and have a large project, we can attempt to reduce detailed planning by dividing the project into phases with a release per phase.

"time estimation"

To be Agile we want to be able to estimate time quickly and re-evaluate our accuracy after each sprint. We can use techniques such as planning poker and we can estimate time in story points or just hours. One difficulty for a team here is intrusions during a sprint which draw hours from the original estimate, this is in some organisations unavoidable . A simple approach to account for this is to estimate a productivity percentage for each sprint. So of we have a team with 500 hours available and a productivity of 50% we will be able to assign 250 hours of tasks to the sprint. At the end of each sprint we can check the outcome and adjust the productivity percentage accordingly.

"what is in and out of the sprints"

Another area which can be difficult to establish is what kind of tasks to we include in the sprints and what kind of tasks lie outside the sprints. We want tasks within our sprints to be determinable so we can assign accurate estimates. Requirements and analysis work in its nature can be difficult to determine, therefore these often lie outside the sprint. Design at a high level of abstraction may also lie outside the sprint with design regarding specific requirements being placed in the sprint. Implementation work and unit testing lies within the sprint. However "integration and regression testing" may lie in or outside the sprint depending on our business model and automated testing support.

"testing and stabilisation"

In a "line based" model we will be expecting to turn out production releases at a high frequency with the benefit being "time to market" for the product. However for this to have a realistic chance of success a high degree of automated test is required since "integration and regression testing" has to be performed in a very short space of time. This may require investment in more advanced testing tools and frameworks.

In a "project based" model delivery to production may be more long term. In this case while automated testing is still favoured, it can be complimented with "stabilisation sprints" where "integration and regression testing" can be performed manually.

"don't be afraid to try"

Don't be afraid to try things that are perhaps not considered fully Agile. Remember that what we are aiming for is a process which helps our organisation get our product to market, on time, at the right quality and on budget. In many cases a "hybrid" Agile process allows the organisation to reduce the impact of change and can allow the process to grow organically with the organisation.

Conclusion

Agile is without a doubt a great platform upon which to base product development but in order to have an Agile process working well in practice the host organisation has to understand its own capabilities, and its business model. All organisations and products are different in nature and there is no "one size fits all", it is likely that the Agile process will require some degree of adaption if it is to be effective and avoid large initial investments. There are a number of concrete principles mentioned previously which can help get the Agile process moving. However the starting point for developing an Agile organisation is to buy into the principles and have your organisation buy into these principles. This provides the foundation for an organisation to be Agile.